Absolutely nothing.

That is the answer to the question in the subject line. It is also the value hedge fund investors receive for shelling out exorbitant fees for lackluster performance.

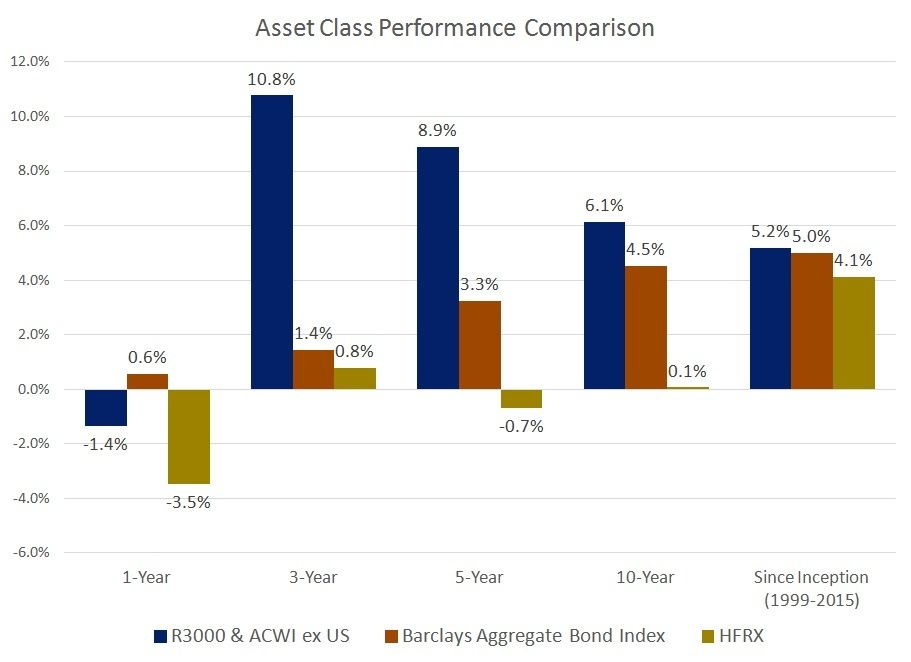

The chart below looks at historical performance of hedge funds (yellow bars) relative to diversified stocks (blue bars) and bonds (orange bars). It’s pretty obvious that hedge fund performance has been relatively poor.

Biases in Hedge Fund Data

The dramatic underperformance is pretty amazing considering the survivorship and backfill biases in the index data that each skew hedge fund returns upwards by three to five percent per year. Both biases stem from the fact that hedge funds aren’t required to report their performance – all reporting is entirely voluntary.

The survivorship bias refers to the fact that hedge fund indices only show the returns earned by funds that are currently in the index. That means the index doesn’t include funds that previously reported returns, but stopped reporting due to poor performance. The implication is that hedge funds only report when they are successful and stop reporting once they have a string of bad results.

Consequently, all hedge fund indices are missing some really bad performance and, thus, hedge fund index returns are artificially high.

Backfill bias also has dramatic impact on various hedge fund indices, including the HFRX Global Hedge Fund Index in the analysis above. Backfill bias occurs when an index provider adds a new fund to their index and “fills in” prior returns of that fund, which are presumably good. For hedge fund managers, this typically means establishing a fund with seed money and then waiting to report results until returns are sufficiently high to start marketing the fund and raise money using the allure of strong past performance. The end result is a process that overstates returns.

Whether you look at an aggregate index such as the HFRX Index or at the performance of a specific strategy, the way hedge funds report data results in the index showing higher performance than was actually realized.

Relative Skill Trumps Absolute Skill

Don’t get me wrong, there are really smart hedge funds managers out there, but absolute skill has less to do with the probability for success than relative skill. Everyone is really smart. Everyone is competing hard for a shrinking pool of excess returns (alpha).

Most hedge fund investors – and by most, I mean 99% or so – think they are somehow able to identify the best managers in advance.

“We only pick the best managers.”

“Our process is second to none.”

“We have access to managers and data that others don’t.”

Mathematically speaking, these statements can’t hold true for everyone. It’s much like how 90% of people think they are an above average driver – in reality, only 50% of people can be above average (note we are talking about the median, not the mean).

So everyone can’t be a winner, but even being above average doesn’t necessarily translate to outsized returns because the distribution of returns isn’t a normal distribution (evenly distributed), but instead returns are heavily skewed such that a handful of managers crush the industry by a significant margin.

The 20 most profitable hedge funds in 2015 earned $15 billion while the rest of the industry lost $99 billion, according to Bloomberg. This isn’t unusual, so good luck picking the winning managers in advance. Only a small group of people have demonstrated any ability in doing so.

The Yale Model

David Swensen, the Chief Investment Officer at Yale, developed a model (popularly known as the Endowment Model or Yale Model) based on modern portfolio theory that invests heavily in alternative and non-liquid investments. Mr. Swensen’s success at Yale has provided the hedge fund industry an example of why people should be using their products and strategies. Unfortunately, replicating the Yale model is unrealistic for 99% of individual and institutional investors.

Yale (and a handful of select competitors) has an entire team dedicating 100% of their time to hedge fund evaluation. Most family offices or financial advisory firms have only one or two people that dedicate themselves to alternatives, but frequently those people have other responsibilities too. In addition, the career risk for most financial advisors is substantially higher than for those endowment employees, which leads to an increased probability of performance chasing and herding behavior.

The Yales of the world have unprecedented access to managers and a level of transparency beyond published updates that other investors simply don’t get. For example, it’s unheard of for anyone other than these big players to receive daily holdings reports or the first phone call from a manager when something is wrong along with an explanation of whether that something is expected to continue or not.

Furthermore, the Yales of the world have the ability to tolerate illiquidity in a way that makes them a more attractive match for hedge funds (thus more access), but it also allows them to sit through years or decades of underperformance. They also have the portfolio size to properly diversify across managers and the clout to structure investment agreements in more favorable terms than the average investor.

So yes, there is a way to increase your odds for success with hedge fund exposure – unfortunately you can’t do it.

The Allure of Hedge Funds

The allure of hedge funds revolves around an ever-changing narrative that plays off investors’ emotions and fears, but always centers on uncorrelated profits with minimal downside risk. Plus, it’s always easier to blame someone else when using a complex investment strategy as opposed to being the only one to blame in years a passive portfolio doesn’t work out.

Hedge fund exposure fails to deliver for investors due to exorbitant fees, high competition, the ineffectiveness of active management, and a general misunderstanding of the underlying exposures and correlations (i.e. hedge funds don’t hedge). But the purpose of hedge funds from the perspective of the manager, parent-company, consultants, and brokerages is to collect fees. In that sense, hedge funds have been a huge success each and every year.

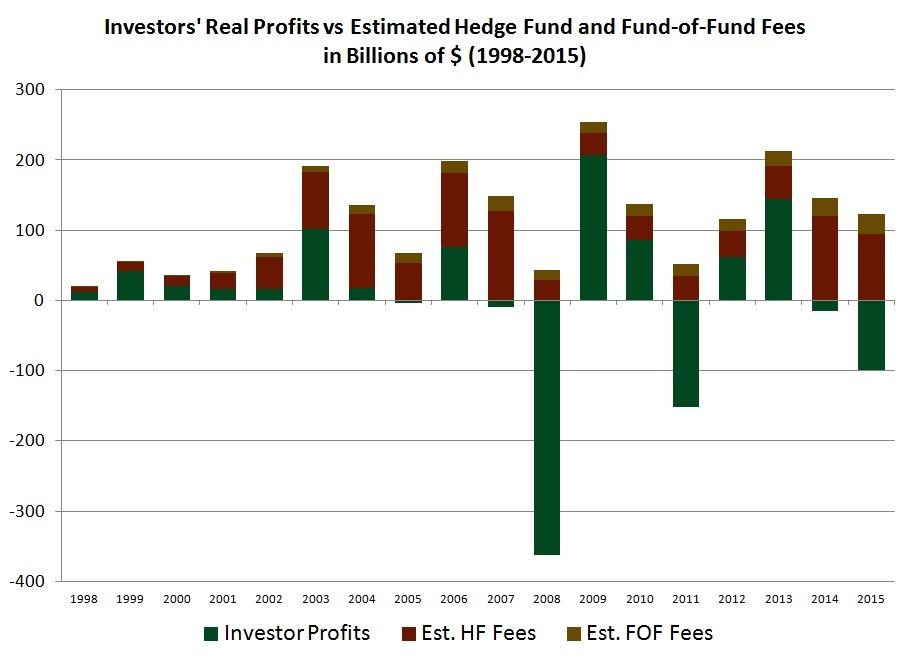

Below is a profit and fee analysis using the methodology from Simon Lack’s The Hedge Fund Mirage: The Illusion of Big Money and Why It's Too Good to Be True and publicly available data from BarclayHedge and Hedge Fund Research.

The methodology understates hedge fund profits for a variety of reasons, but you can still see that running a hedge fund has been a good business in good and bad markets. In fact, Simon Lack’s most recent data shows that hedge funds captured 84% of the profits and fees from 1998 through 2014 versus investors that only captured 5% (fund of funds captured the remaining share of industry profits).

Conclusion

So let’s revisit our original question. Hedge Funds: What are they good for?

Absolutely nothing is probably still the accurate response for most investors. For the managers, parent-companies, consultants, and brokerages that collect fees, it is a money tree.

Related reading:

The Collective Knowledge of Financial Markets

The Failure of Active Management

Sources and Disclosures:

Russell 3000 Index® measures the performance of 3,000 publicly held U.S. companies based on total market capitalization, which represents approximately 98% of the investable U.S. market.

MSCI All Country World ex-U.S. Index® captures large, mid and small cap representation across 22 of 23 Developed Markets countries (excluding the United States) and 23 Emerging Markets countries. With 6,161 constituents, the index covers approximately 99% of the global equity opportunity set outside the U.S.

The Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index® covers the USD denominated, investment-grade, fixed-rate, and taxable areas of the bond market. This is the broadest measure of the taxable U.S. bond market, including most Treasury, agency, corporate, mortgage-backed, asset-backed, and international dollar-denominated issues, all with maturities of 1 year or more.

HFRX Global Hedge Fund Index is designed to be representative of the overall composition of the hedge fund universe. It is comprised of all eligible hedge fund strategies; including but not limited to convertible arbitrage, distressed securities, equity hedge, equity market neutral, event driven, macro, merger arbitrage, and relative value arbitrage. The strategies are asset weighted based on the distribution of assets in the hedge fund industry.

Index performance returns do not reflect any management fees, transaction costs or expenses. Indexes are unmanaged and one cannot invest directly in an index.

PAST PERFORMANCE IS NO GUARANTEE OF FUTURE RESULTS. Investing involves risk. It should not be assumed that recommendations made in the future will be profitable or will equal the performance shown. Investment returns and principal value of an investment will fluctuate and losses may occur. Diversification does not ensure a profit or guarantee against a loss.

A version of this article originally appeared on CFA Institute's Enterprising Investor.