New ideas are always difficult to accept at first. This is never more true than when those new concepts conflict with our existing beliefs.

When seeking to understand the world around us, our brains are hardwired to take the path of least resistance. We naturally prefer to emphasize mental efficiency and avoid any distress caused by not understanding an idea or concept.

Our brains also don’t like to admit this is what we’re doing. You might read those first couple paragraphs and think, “It makes sense that other people do that. But I don’t think that way!”

The truth is, we’re all susceptible to this mental rigidity. As a result, it can be difficult to accept and incorporate new information into our lives – even when those new ideas could positively impact our finances.

Facts Don’t Matter When Feelings (and Mental Rigidity) Get Involved

When working with clients, mental rigidity seems to show up most often when a client wants to eliminate the uncertainty that arises from any given situation. This desire motivates them to find a quick, easy-to-understand answer to their questions.

The greater the need for an answer that fits into their view of the world, the more energy the client usually puts into accepting and defending whatever that answer may be – even if evidence suggests the answer is not true.

If you are having a hard time picturing what this looks like, consider this conversation between mathematician George Vaccaro and Verizon representatives about the difference between dollars and cents:

Maybe the representative and his manager truly didn’t understand their mistake in quoting and calculating the data usage rate (although I find that hard to believe, as the customer laid it out pretty clearly).

But what’s notable here is that the more the Verizon representatives committed to their beliefs, the harder it became for either of them to say, “Oh my gosh, you’re right. I made a mistake in my thinking; my first impression was wrong. Now I understand what you’re telling me.”

Many people do the exact same thing when evaluating their investment strategy.

Do Your Beliefs Blind You to What the Evidence Shows?

Imagine your portfolio is trailing the S&P 500. If you are a globally diversified investor with any sort of a bond allocation, then this scenario shouldn’t be too hard to imagine.

How much this tracking error (which is the technical term for differences in your portfolio’s performance and a given benchmark) agitates an investor will vary from person to person. Unless you put all your money in the S&P 500, your performance is obviously going to look different from month-to-month, quarter-to-quarter, and year-to-year.

But there is an enormous amount of evidence suggesting that global stock diversification and bond exposure are prudent investment decisions. Still, many investors I speak with seem skeptical about this fact.

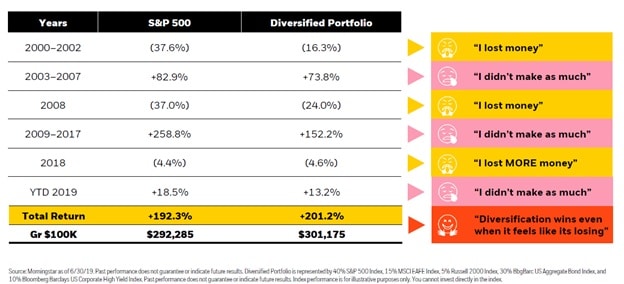

This chart from BlackRock resonates with me because it serves as a pretty spot-on outline of the agitated investor’s feedback I’ve seen play out time and time again throughout my career:

It’s one thing to agree to a long-term investment plan at the onset of a relationship with a financial advisor, but the actual experience of riding out different market movements is harder in practice than in theory.

As you can see in the graphic from BlackRock, there was always a reason to be upset if you had a globally diversified mix of stocks and bonds.

Sometimes you lost money. Sometimes you made money — but not as much money as the S&P 500. Other times you lost more than the S&P 500.

But despite the variety of reasons to be disappointed with your portfolio’s performance, the diversified portfolio actually won over the entire period. It’s hard to notice the benefits of diversification in the moment because being well-diversified means there will always be a part of your portfolio you hate.

This extends well beyond the case for diversification.

For example, the empirical case for maintaining a long-term overweight to value stocks is robust, but watching value stocks lose to growth stocks in the U.S. in the last decade might cause an investor to conclude that the world is changing and fundamentally different than the past.

Constant change has always been a part of investing. There has never been a moment in market history where the world didn’t seem fundamentally different than prior decades.

What hasn’t changed is that probability is the only rational way to make decisions about an unknown future.

In the case of global diversification or value investing (the two examples from above) the probabilities suggest that a decade like the one we just had is not unusual, but the probabilities also suggest investors that remain disciplined with those strategies will be rewarded.

The True Value of a Financial Advisor

Here’s the dangerous reality when it comes to portfolio construction: the perfect portfolio means nothing if the investor ignores the evidence.

I don’t believe an advisor’s value from an investment perspective comes from his or her investment selection prowess.

An advisor’s ability to minimize mistakes and get you to stick with a long-term plan is the single greatest skill you should look for.

It’s what makes being a good advisor so difficult.

At the end of the day, it’s still only you that can make the right decision. It is your money and ultimately your choice in what you do with it. A good advisor may give you the right guidance, but your mental rigidity may cause you to ignore it.

The takeaway isn’t that you should be less rigid. You can’t take human nature out of humans, after all.

But what you can do, and what I highly recommend, is to focus more on understanding your tendencies and how they could hurt you if you’re not aware of what’s driving your emotions and therefore your behavior.

Now that’s an investment conversation to have with your advisor that will bear more fruit than debating whatever it is you think will move the market next.

.png?width=858&height=450&name=Blog%20Banner%20Images%20(1).png)

-4.png?width=266&name=Copy%20of%20blog%20featured%20image%20(1)-4.png)